Reduce Access to Prescription Drugs

Return to Opioid Top-Level Strategy Map

One of the reasons people begIn misusing opioid pain medication is the drug can be easy to access for appropriate, prescribed medical use. There are a multitude of reasons for the legitimate use of opioids under the close care of medical professionals. We must prioritize dual efforts, making sure we reduce access to those prescription opioids for those who might misuse while making sure patients who need opioids are able to access them.

Contents

Background

Understanding more about how people access opioids, especially prescription opioids, can help us understand how we can reduce access.

Sources of Opioids for Non-Medical Use (Misuse)

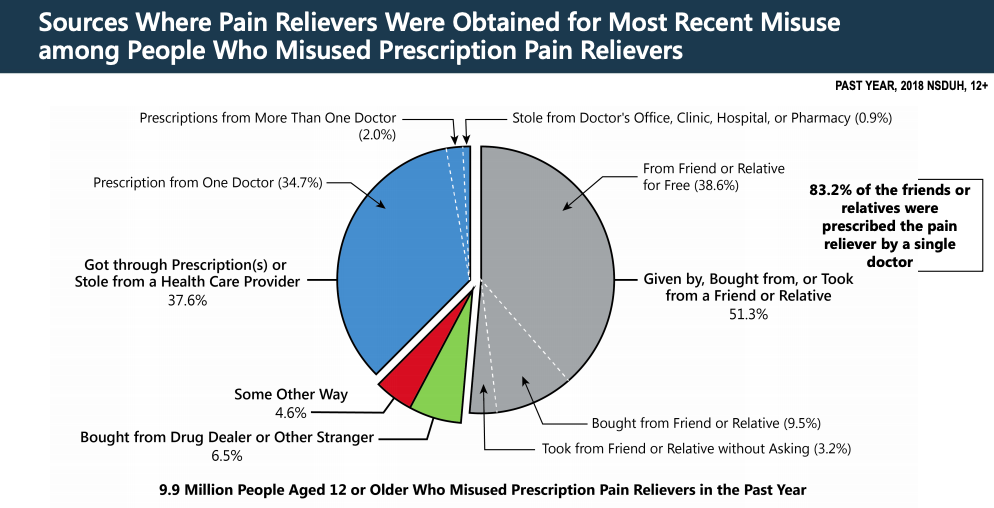

The vast majority of misused prescription opioids come from friends and family of the person misusing through both intentional and unintentional diversion. The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicated that more than half of people misusing opioids received their prescription opioids through these methods. Only 6.5% sourced their prescription opioids from a drug dealer.

Source of Graphic: SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018.

According to the NSDUH survey of people who misused pain relievers, the majority (51.3%) responded that they received them from a friend or relative.[1] Even though these numbers are slightly decreased from the 2017 NSDUH survey, the fact remains that the most prevalant "drug dealer" of prescription opioids are friends and relatives

- 38.5% received them from a friend or relative for free.

- 10.6% purchased them from a friend or relative

- 4.0% took them from a friend or strange

Reasons for Opioid Non-Medical Use (Misuse)

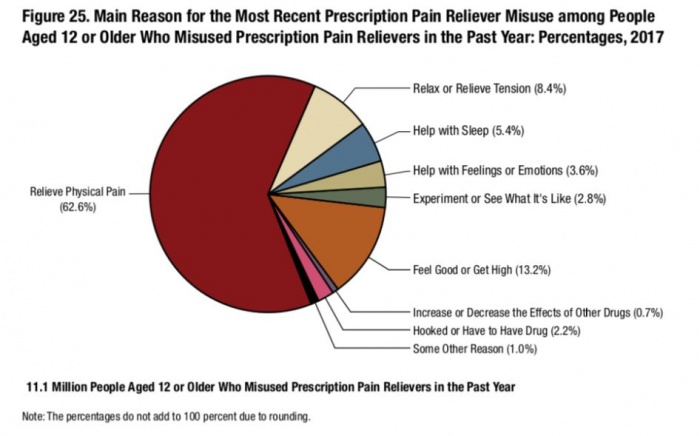

The 2017 NSDUH survey also examined why people were misusing prescription pain medication. That data indicated the primary reason (62.1%) people are misusing precription opioids is for pain.

Source of Graphic: SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2017.

It would be helpful to have (or find) better research on this, but given that this poll showed that 62.6% of the people who misused prescription pain relievers claimed to have done so for pain[2], it would seem plausible that the person giving them their own prescription pain relievers were trying to help them deal with the pain, not trying to help them get high or feed an addiction to aviod withdrawal symptoms.

This data would suggest an important strategy issues:

- A strategy to reduce prescription drug misuse should include a strong emphasis on educating people to not give or sell their medications to anyone else. This might include educating people on how they can best respond when a friend or relative approaches them to get prescription pain medication to help them address their pain problem.

- The single most effective way people can impact the opioid crisis is to safely dispose of their medication as soon as practicable. A strategy should emphasize prompt disposal of pain medications after their prescribed use is no longer needed. If people quickly dispose of their presecription pain medications when they are not necessary, they would be less likely in a situation where a friend or relative who was struggling with pain (or perhaps pretending to struggle with pain or who was struggling with pain related to withdrawal) would be able to divert the opioids for misuse.

- People who might be approached by friends and relatives who are seeking access to pain medications (the #1 source based on the NSDUH) should become important actors in a strategy that emphasizes helping people before their brains have been changed due to ongoing use or misuse of opioids. A good strategy would equip these people with ways to help their friends and relatives with both physical pain and with ways to get help for other factors that may be driving misuse of opioids.

Opioid Access and Misuse Among Teens is Decreasing, but Remains Concerning

The 2017 Monitoring the Future survey of 8th, 10th and 12th graders shows encouraging news -- it's getting harder for teens to access prescription opioids. Only 35.8 percent of 12th graders said they were easily available in the 2017 survey, compared to more than 54 percent in 2010[3] Overall, 43,703 students from 360 public and private schools participated in this year's MTF survey.[4]

Opioid misuse is also decreasing. For example, among high school seniors, past-year misuse of pain medication, excluding heroin, decreased from a peak of 9.5 in 2004 to 3.4 percent in 2018. The past-year misuse of Vicodin decreased from a peak of 10.5 percent in 2003 to 1.7 percent in 2018, and Oxycontin misuse has decreased from the peak rate of 5.5 percent in 2005 to 2.3 percent in 2018. Furthermore, students in the 12th grade believe that opioids are harder to obtain than in the past. In 2010, 54 percent of students in 12th grade believed that these drugs were easily accessible, as compared to 32.5 percent in 2018.[5]

Death from overdose is the most serious consequence of prescription drug misuse. And while the number of deaths from drug overdose remains quite low overall, the rate of overdose deaths among adolescents is increasing. In 2015, 4,235 youth ages 15-24 died from a drug-related overdose; over half of these were attributable to opioids.[6]

The health consequences of opioid misuse affect a much larger number of young people. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that for every young adult overdose death, there are 119 emergency room visits and 22 treatment admissions.[7]

Tools and Resources

Solutions and Tools focused on this objective.

Promising Practices and Case Studies

Actions to Take

Coordinate a Local Drug Disposal and Take-Back Program

Starting a drug take-back event or program requires coordination across government, private pharmacies, law enforcement, and community members. The Safe Drug Disposal Guide for Communities from the Drug Enforcement Administration and Partnership for Drug-Free Kids is an introduction to the issue of safe drug disposal programs. It is written to help community officials and organizers design a safe drug disposal program for their community, identifying federal guidelines and processes. Each community will need to adapt for its local needs, regulations, and resources, but this is a solid start with a focus on consumers, pharmacies, and law enforcement.

Coordinate with Local Water Treatment Project on Disposal

While flushing opioids down the toilet does prevent them from being diverted, it creates a new problem for communities when opioids and toxic medications end up in the water system because there are not effective ways to clean or filter them. Communities can mobilize their water treatment programs to increase awareness of proper disposal methods for prescription medicines, which often end up in the water system through flushing or drain dumping. By working with water treatment facilities on education, resources can be aggregated to build awareness that benefits everyone.

Create Customized Medication Fact Sheets

Until prescribing of opioids is reduced and remains low, patients are their own best weapon for preventing opioid dependence. Many patients rely heavily on their doctors to know and inform them of all of the risks, but this epidemic has demonstrated the need for all of us to be armed with information. These fact sheets will help patients understand the risks, how to increase safety for themselves and others, and seek alternative treatments. Customized medication fact sheets can include a variety of information promoting safe handling, use, and disposal of categories of prescription medicine. Include tips such as: don’t share your medications, questions to ask your doctor, names of different medications in the category covered, and lower-risk alternatives. Statistics can include a mix of data from sources such as the CDC on risks associated with non-medical use, as well as state or local statistics. Information about disposal is best when customized to the location. Alaska has a good example. SAFE Project also has fact sheets available on Opioids, Your Pharmacist and Your Safety, and Benzodiazepines. Community pharmacies and clinics are best positioned to share this information in person to answer any questions people may have. Fact sheets can also be offered on local health-focused websites or made available for download.

Create Safe Prescription Storage Fact Sheets

Educating the community on proper prescription drug storage is the number one step community members can take to reduce non-medical use of medications. Most people do not know how to dispose of medication and, more important, do not lock up their medications. This increases the risk of poisoning, diversion, and non-medical use. Develop a fact sheet describing the dangers of storing prescription medications improperly that includes easy-to-understand information about how to safely store and dispose of medications, local resources for acquiring locking medication bottles, disposal pouches, and disposal lock-box locations. Refer to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines for safe storage or the Food and Drug Administration’s guide to medicine safety.

Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Opioids Checklist

Doctors are increasingly pressured for time in patient visits and may feel as if they don’t have time to go over the risks involved with taking opioids. For patients with a history of substance use disorder, mental health histories, or even at-risk family members, reviewing concerns with doctors is particularly important. When a patient and their doctor discuss these topics along with possible alternatives, it can save lives, prevent dependence and addiction, and potential non-medical use. The Food and Drug Administration has a one-page form with questions to ask your doctor and is a great reminder tool for patients. This opioid-focused checklist can be printed and handed out or posted at doctors’ offices, pharmacies, or prevention, treatment, and recovery services to support protective behaviors. The questions are great for preventing opioid use disorder, as well as for initiating conversations between at-risk patients and their providers.

Sources

- ^ https://www.legitscript.com/blog/2018/09/nsduh-report-opioid-abuse/

- ^ https://www.legitscript.com/blog/2018/09/nsduh-report-opioid-abuse/

- ^ https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2017/12/vaping-popular-among-teens-opioid-misuse-historic-lows

- ^ https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2017/12/vaping-popular-among-teens-opioid-misuse-historic-lows

- ^ Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975-2018: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2018.pdf

- ^ The National Institute on Drug Abuse Blog Team. (2017). Drug overdoses in youth. Retrieved from https://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/drug-overdoses-youth.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2016). Abuse of prescription (Rx) drugs affects young adults most. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/abuse-prescription-rx-drugs-affects-young-adults-most?utm_source=external&utm_medium=api&utm_campaign=infographics-api.